Is Hydrogen a viable fuel source for Northern Ireland?

In July 2017, the UK government made the announcement that the sales of all petrol and diesel-powered vehicles would be phased out and banned by 2040, due to the negative impacts of emissions on both public health and the environment.

But what does this mean for consumers in Northern Ireland, located in regions where there is a huge reliance on private transport? Many developed countries are now working on creating alternative energy sources for transportation to replace fossil fuels.

At present, there are two promising technologies at the forefront of alternative energy; Electric Vehicles (EVs) and Fuel Cell Vehicles (FCVs). For some time, global car manufacturers have been electrifying selected vehicle models and whilst the infrastructure for these has its drawbacks, it is more advanced than that of hydrogen, which powers FCVs. However, with an increasing amount of research and projects, hydrogen is growing in popularity as a viable alternative fuel source to the ongoing fight towards decarbonisation and emissions reduction.

The past, present, and future of alternative fuel technologies

Before looking at hydrogen, it is important to look back at the history of Northern Ireland’s Electric Vehicle charging infrastructure. An initial run of EV charging points was installed in 2012, with 40 installed in towns across the country. Another 140 were added a year later and a further investment of £600,000 was made in 2014 to install 100 EV charge points at hospitals, health trusts, libraries and local council offices. Currently, there are around 350 public charge points available across NI.

But many issues around EVs remain. One major issue surrounds range anxiety. Despite improvements in battery technology, there is still a fear that on a long journey you may run out of power or have to stop for an extended period of time to recharge. Some research has been carried out to try and help mitigate this – the EU funded BATTERIE project developed an e-car journey planning tool which helps to plot a journey and point you to charge points. A trip from Belfast City Hall to Trinity College Dublin, with a 100% charge at the beginning of the journey would take 2 hours including one stop for a rapid charge, and see you arrive at your destination with around 40% of battery remaining. This relies on the availability of the rapid charger – a standard charger would add several hours in waiting time to the journey. In comparison to the same journey in a traditional car, which takes approximately 1 hour 40 minutes, using less than one full tank of petrol or diesel.

For many, this is where hydrogen could come into play. According to researchers, the range of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles tends to be more economical than EVs. For instance, Hyundai’s hydrogen fuel cell vehicle, the Nexo, comes with a range of 414 miles and takes five minutes to refill, compared to that of its electric counterparts which can often take up to an hour. However, whilst some car manufacturers, such as Hyundai and Toyota, remain confident that hydrogen technology now represents the future of transport, it is still considered too complicated for mass adoption.

Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles (FCVs) – How do they work?

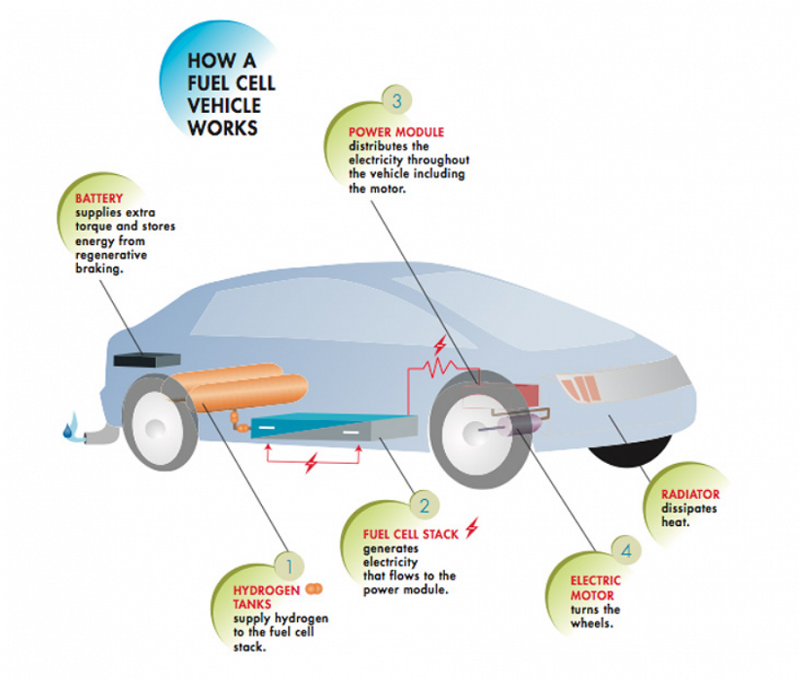

Hydrogen is considered the most abundant element on the planet. However, it doesn’t exist on Earth as a gas by itself, but instead, usually makes up part of another component, such as water. The gas is usually produced using the common method of steam reforming, using natural gas, or by sending an electrical current through water in a process called electrolysis. Once separated from the other components, it can be used with oxygen in a fuel cell to create electricity, providing an alternative fuel source to power vehicles.

An FCV is like an EV in that they are both powered by an electric motor. However, electricity is stored in a battery in an EV, whereas the FCV produces electricity through a chemical process inside the fuel cell. The hydrogen then acts as a replacement for petrol or diesel, refuelling in exactly the same time traditional fuel does. This contrasts with EVs, which take considerably longer to recharge.

Source: How does a hydrogen fuel cell vehicle (FCV) work

Where are we now?

Hydrogen as an alternative fuel source is far from a new concept. In fact, the first hydrogen-powered vehicle is often credited to General Motors, which developed its GM Electro-van vehicle back in 1966. However, the project was scrapped at the time, due to cost concerns. Since 1966, various automakers have experimented with the innovative fuel source. In fact, today, the Japanese carmaker, Toyota, introduced the world’s first mass-produced hydrogen fuel cell car to the road. Yet, despite the enthusiasm shown by some automakers, concerns surrounding hydrogen’s feasibility has meant the overall development of the fuel cell technology has been slow. As a result, it remains several years behind EVs in terms of innovation, due to fears around cost, the lack of refuelling infrastructure and storage difficulties.

Despite this, there is already proof that hydrogen technology is gaining traction, especially in larger vehicles such as buses, lorries and fleet vehicles. Several hydrogen buses have been running in London since 2010, and the UK’s Transport Secretary is now looking to add hydrogen trains to the network. Similarly, hydrogen buses have also been introduced in Aberdeen. Both examples provide evidence of how Northern Ireland could potentially adapt its own public transport infrastructure to accommodate a hydrogen-powered future – we even have Wrightbus, one of the major producers of hydrogen buses, located on our doorstep.

Hydrogen and EU Projects

Research projects surrounding the technology are also gaining momentum. There are several EU funded projects that we are currently partners of. These aim investigate the feasibility of hydrogen as a fuel source to power vehicles. One of which is SEAFUEL, where an electrolyser is being installed on an island site, linked to wind turbines and solar panels with no connection to the grid. However, this does mean that a hydrogen fuelling station must be located close to the renewable energy installation, which may not appropriate if the fuel is being produced in Fermanagh for example and needs to be used in buses that are running to Belfast.

Another EU funded project is HUGE, which aims to investigate the supply chain for hydrogen across the Northern Periphery of Europe, having identified that suppliers and end-users may not be conveniently located together. The project hopes to identify hydrogen hotspots across the region and develop ways in which the hydrogen economy can grow and mature.

What does the future hold for FCVs?

Despite the many false starts and the reservations that still surround FCVs, researchers have renewed their interest in hydrogen technology, due to its potential as a pollution-free fuel. The continued success of other renewable technologies has shown that with some innovation and policy incentives, hydrogen could become a key player in helping build our global clean energy industries.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA):

As an island location, Northern Ireland is suited to the development of an economy, reliant on renewable energy, with a mixture of EVs for short commutes and FCVs for longer commutes. Overall, whilst the development of FCVs for private transport remains at a relatively immature stage in comparison to EVs, the UK’s target to make all transport fossil fuel by 2040, alongside the recent formation of a Hydrogen Council, where companies including Toyota, Honda, Daimler, and BMW have committed to the investment in hydrogen research and lobbying - a hydrogen-fuelled future may be closer than we think.